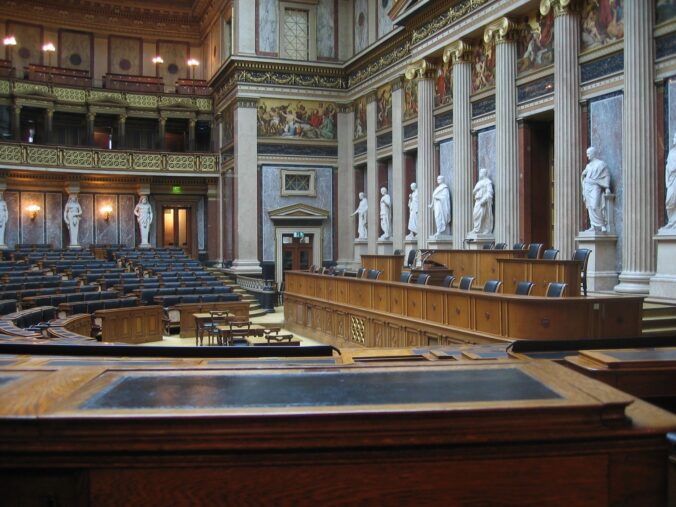

60 years ago this month, James Baldwin and William Buckley met in person to debate the motion, “The American Dream is at the Expense of the American Negro.” Baldwin won the debate and the motion was carried, 544 to 164.

The Debate was a defining moment in American intellectual and political history, particularly in the 1960s, during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Baldwin, an African American writer and social critic, powerfully articulated the reality of racism and the plight of Black Americans. Baldwin argued for the urgent need to address the systemic inequalities causing oppression. Buckley, defending a conservative perspective, asserted that societal change should be gradual and that Black Americans should work within existing structures for progress.

Baldwin’s approach was forceful, emphasizing the dehumanizing effects of racism and the need for an honest reckoning with the history of slavery, segregation and oppression. He eloquently articulated the psychological toll of living as a Black person in America, addressing not only the physical violence of racism but also its more insidious, everyday forms. His rhetoric was impassioned, calling on America to recognize the full humanity of Black people and to confront the unresolved injustices of its past.

Some notable quotes from Baldwin:

“The American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro. I picked the cotton, and I carried it to the market, and I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing.”

“The real question is really a kind of apathy and ignorance, which is the price we pay for segregation. That’s what segregation means. You don’t know what’s happening on the other side of the wall because you don’t want to know.”

“I am not a ward of America. I am not an object of missionary charity. I am one of the people who built the country. Until this moment, there is scarcely any hope for the American Dream.”

In contrast, Buckley’s arguments were rooted in a belief in gradualism, the idea that social change should not disrupt the existing order, and that the push for equality could lead to societal instability. Buckley expressed concern about the speed of the Civil Rights Movement, fearing that it could result in chaos or undermine the foundational values of American society.

In response, Buckley often directly addressed Baldwin; quotes from Buckley include:

“We must also reach through to the Negro people and tell them that their best chances are in a mobile society. The most mobile society in the world is the United States of America. And it is precisely that mobility which will give opportunities to the Negroes which they must be encouraged to take.”

“The fact of the matter is that the animadversions against America . . . by Mr. Baldwin come out in a long and predictable continuum of such complaints, most of them unjustified.”

“It is quite impossible in my judgment to deal with the indictment of Mr. Baldwin unless one is prepared to deal with him as a white man, unless one is prepared to say to him the fact that your skin is black is utterly irrelevant to the arguments that you raise.”

Baldwin’s arguments won the day, receiving, as stated, 544 votes to Buckley’s 164.

Though once thoroughly trounced, Buckley has been revived. His arguments, rooted in a denial of history that pretends vestiges of the past do not shape the present, have found new life in so-called “Anti-DEI” campaigns. One hears the agents of the new administration echoing Buckley:

“I think the single dumbest phrase . . . is our diversity is our strength.” – US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth

“My administration has taken action to abolish all . . . diversity, equity and inclusion nonsense – and these policies [are] absolute nonsense – through the government and private sector.” – President Donald Trump

We now find ourselves in 1965. Unfortunately, the voting audience is not now educated. This poll is being taken in places where 1965 isn’t back far enough.

We, you and I, must change that vote.

We must resist with the truth and by building community.

We must build anew.